Running on empty? The strategic impact of political instability in Romania

On 5 October, the lower and upper chambers of Romania’s parliament voted in support of a no-confidence motion in the minority government led by Prime Minister Florin Citu’s centre-right National Liberal Party (‘PNL’), thereby precipitating its collapse.

The vote followed weeks of political paralysis. At the beginning of September, the liberal centrist Save Romania Union and Freedom Unity and Solidarity Party alliance (‘USR-PLUS’) resigned as junior partner in the coalition government, which had been formed together with PNL and the Democratic Alliance of Hungarians in Romania (‘UDMR’) in December 2020.

The resignation of USR-PLUS from the ruling majority was triggered by a dispute over the ‘Anghel Saligny’ programme, which earmarked EUR 10 billion in funds for local development. USR-PLUS opposed the programme, claiming that it was a means for Citu to buy the support of PNL mayors ahead of a race for the party leadership, which he subsequently won from his former patron; the speaker of parliament’s lower chamber and former prime minister, Ludovic Orban.

In order to facilitate the passage of the funding, Citu solicited the dismissal of the USR-PLUS justice minister, Stelian Ion, who had also fallen afoul of President Klaus Iohannis over disagreements regarding judicial reforms. This was the final straw for USR-PLUS, which had already seen Citu oust its health minister in the spring.

The government was an unhappy cohabitation from the beginning. Prima facie it enjoyed the rare advantage that the presidency, cabinet and parliament were all controlled by the ruling majority, which had not been the case since 2004. Furthermore, it was formed on a centrist basis, seeking to reverse the mismanagement, populism and institutional backsliding that was endemic under the coalition government led by the Social Democratic Party (‘PSD’) between 2016-2019.

But after a year of minority government by PNL that had struggled to demonstrate much more competence, and record low turnout, both PNL and USR-PLUS undershot expectations in the election. Indeed, PSD was able to remain in first place despite having been hollowed out by its authoritarian leader, Liviu Dragnea, who was ultimately pulled out of politics by a corruption conviction. Elsewhere, the far-right Alliance for the Union of Romanians (‘AUR’) unexpectedly entered parliament with 9% of the vote.

Political outlook

Following the no-confidence vote, President Iohannis convened all party leaders to discuss the appointment of a prime minister. At present, there are three scenarios with respect to government formation going forward.

The first scenario is the negotiation of a new ruling majority between PNL, USR-PLUS and UDMR. This would be the preference of USR-PLUS, which wants to reconstitute a new government, albeit without Citu as prime minister. Although Citu consolidated his leadership of PNL last week, his position within the party could be easily weakened by the faction aligned with Ludovic Orban, whose MPs abstained in the no-confidence vote.

However, USR-PLUS had originally negotiated its coalition with PNL on the condition that Orban would not continue as prime minister. More likely, President Iohannis – who is the main backer of Citu – would appoint a proxy.

Yet there is little indication that PNL and USR-PLUS are prepared to offer each other much in the way of compromises. For example, USR-PLUS – which recently fully merged – has appointed former prime minister Dacian Ciolos as its leader, potentially returning him to national politics after two years in the European Parliament. A reformist technocrat, Ciolos is not likely to undermine the diminishing prospects of his party without significant concessions from PNL.

The second scenario would emerge from a failure to negotiate a new majority between PNL and USR-PLUS. Citu would lead a minority government with the tolerance of PSD, which would likely gain the speakership of parliament’s lower chamber. Such an arrangement would be highly damaging for PNL, the ratings of which are already far below those of PSD.

Government effectiveness would be further impeded by the need to negotiate majorities for legislation on a case-by-case basis, although PNL would be able to rely on emergency ordinances. These can only be overturned by the Constitutional Court by way of the Ombudsperson; however, the current Ombudsperson, Renate Weber, has repeatedly clashed with the Citu government over such practices, to the extent that the ruling majority unsuccessfully attempted to remove her from office.

The third scenario would involve the calling of early elections. According to the polls, PSD would profit most from such a situation, capitalising on the deep disaffection with PNL and USR-PLUS that would inevitably lead to the low turnout from which the party, with its loyal voter base, has historically benefitted. It is plausible that PSD would form a populist coalition with AUR in the wake of an early election.

However, precisely because it is not in the interests of either PNL or USR-PLUS, a snap election is unlikely. President Iohannis, who is the most powerful politician in the country, will attempt to exhaust every alternative in order to avoid such a scenario. It is noteworthy that, although there have been fourteen governments in Romania since 1992, there have only been eight parliamentary elections – none of which were held before they were scheduled. Political differences tend to be resolved on the negotiation of new majorities on an opportunistic basis, rather than through snap votes.

Old demons, new challenges

The current course of events is nothing new in Romania. Ruling majorities have always been brittle. Although the political landscape of the post-communist era appears to be split between the descendants of Nicolae Ceaucescu’s regime (currently hosted by PSD) and reformist liberals (represented by PNL and USR-PLUS), with some smaller nationalist parties variously serving as kingmakers (such as UDMR and AUR), this belies the clientelist reality of Romanian politics. Parties negotiate majorities opportunistically in order to serve the interests of their clientele and according to lowest common denominators, such as the unseating of a common enemy.

Extremist forces such as AUR are also not unprecedented when disaffection is high. For example, in 2000, the ultranationalist Greater Romania Party benefitted from four years of chaotic reforms under a centre-right, anti-communist alliance, rocketing by 15% to over 20% of the vote to become the second-largest parliamentary force, before flopping again in 2004. Nonetheless, the political instability that Romania is currently experiencing is increasingly damaging. Previously, poor governance was offset by clusters of innovative activity locally – such as in regional cities – as well as strong fundamentals such as the quality of the workforce, the industrial base, and the wealth of natural resources. European funds and foreign expertise also drove development.

Meanwhile, the various parties were at least united by the common goal of joining NATO and the European Union, even if the policies that accompanied those objectives were often formalistic. Now the parties are at the point where each one has barely any overlap with the others, with multi-polarisation deepening amid uncompromising personality conflicts and power struggles.

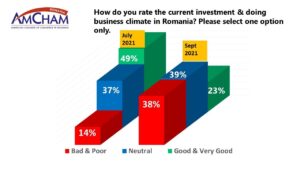

This is highly damaging for strategic decision-making, which is especially urgent in light of the covid-19 pandemic and the ensuant economic crisis. Political instability does not exist in a vacuum; the foreign investors on which the Romanian economy is reliant are increasingly alarmed by the dysfunction, as a survey conducted in September by the American Chamber of Commerce revealed:

It is also impacting macroeconomic indicators. Immediately prior to the collapse of the Citu government, the National Bank of Romania increased the monetary policy interest rate by 0.25% to 1.5%, a move that amid the highest inflation since 2011 was expected – but not the timing. And without a government to take effective budgetary measures (which indirectly include increasing the low vaccination rate), inflation will continue to be exacerbated by the budget deficit, which in the first half of 2021 was reduced but stubbornly high at 2.96% of GDP.

There will also be an impact for the approval and implementation of the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (‘PNRR’), which will pump EUR 29.2 billion of grants and loans into an array of projects. The European Commission signed off on the PNRR last week, but its final form must still be formally approved by a mandated – as opposed to interim – government. The implementation of the PNRR had already been disrupted by PNL ousting USR-PLUS personnel in the relevant ministries.

All three scenarios under the current circumstances will very likely delay the process further. New elections will turn it on its head altogether; but if PNL manages to negotiate a new majority with either USR-PLUS or PSD, key elements of the plan will need to be renegotiated, potentially holding up the entire package, with the burden for existing projects falling on the budget.

USR-PLUS, in particular, would reemphasise the need for the PNRR to be accompanied by judicial as well as other institutional reforms to maximise the efficiency of the funds’ distribution.

Managing expectations

As such, the outlook for government stability is negative regardless of which of the three scenarios transpire. PNL might be able to limp on, but for as long as the main parties are primarily concerned with simply occupying government, there is unlikely to be significant change with respect to the strategic stalemate in which Romania finds itself. Economically, governments may muddle through, but amid a secular decline in the country’s attractiveness as an investment destination.

Marcus How is the Head of Research & Analysis.

This article was originally published on SEENews.

Image source: Florin Citu speaking in Parliament ahead of censure motion vote Source: FB