Brückenbauer? Austrian foreign policy in Central and Eastern Europe

Executive summary

By Marcus How

- Austrian foreign policy has historically been shaped by its constitutional neutrality, which has created a preference for maintaining “equidistance” between geopolitical blocs even as this has become unviable due to EU membership.

- Austria has longstanding historical and cultural ties with CEE, which it maintained through the Cold War and deepened after 1989.

- Despite this, its influence in CEE has waned due to a decline in proactive engagement, confused security policy, and domestic political factors.

- The proliferation of illiberal politics in CEE is creating openings for Austria’s far-right to form geostrategic alliances, especially after the 2024 parliamentary election.

Introduction

In April 2022, the Austrian chancellor, Karl Nehammer, visited Kyiv, where he met Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky. The Russian invasion of Ukraine had begun some six weeks earlier, and the international community was reeling from the massacres committed in the town of Bucha. While there, Nehammer’s closest advisors encouraged him to travel spontaneously to Moscow to meet with Vladimir Putin, where he could confront the Russian president over Bucha while securing Austria’s continued access to the gas its flagship energy company OMV contracts from Gazprom.

The expectation was that Nehammer would be able to position Austria in its historical role as “Brückenbauer”, a bridge-builder between East and West. The Kremlin accepted the invitation, with Nehammer becoming the first – and, until Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban’s visit in July 2024 – the only European head of government to visit Russia since the beginning of the full-scale war.

However, any illusions as to Austria’s role were dashed. The reception was unfriendly, with Nehammer facing Putin from the distant end of the Russian president’s notoriously long table. Nehammer was mocked by the Russian press as a Western lackey who was simpering cynically for favours, in addition to being criticised by much of the Western media for legitimising Putin.

The episode underlined Austria’s overestimation of its geopolitical profile. Its politicians continue to repeat that Austria has a special role to play on the global stage, especially in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), where it can act as a mediator. This is not entirely delusional, as Austria has niche geographical expertise. Yet the cornerstone of its foreign policy, namely its bridge-building, has become increasingly obsolete since 1989 – and nowhere is this more evident than in CEE.

Historical inheritance

Since 1945, Austria’s foreign policy has been shaped by three primary factors:

1. Gateway location

Austria shares a common cultural and geographical heritage with many states in CEE, nine of which had territory that was encompassed by the Austro-Hungarian empire, and twelve of which fall within the basin of the Danube River. Four of its seven borders are with CEE states, nearly half of the entire length. Historically, these borders were notional, with minorities from all national groups of the empire scattered across its territory, until they were painfully uprooted between 1918 and 1950.

2. Neutrality

After 1918, the First Republic of Austria was formed, but it was unstable, eventually being annexed by Nazi Germany in 1938. In 1945, it was liberated by the Allies, whereupon the Second Republic was established. For 10 years, it was under occupation, with the country and its capital Vienna divided up between the USA, UK, France, and the USSR.

In 1955, the Allies negotiated the “Staatsvertrag” (Independence Treaty) with Austria, which ended the occupation, thereby bestowing full sovereignty upon the Austrian state. Unlike its CEE neighbours, it was understood as belonging to the Western European community of democracies. However, in order to secure Soviet backing for the Staatsvertrag, a compromise was necessary: namely, Austria’s commitment to neutrality, which prevented it from joining any military alliances (i.e., NATO) or political unions (i.e., the processes of European integration). “Immerwährende Neutralität” (perpetual neutrality) was subsequently enshrined in the constitution.

3. “Equidistance”

Austria’s erstwhile “equidistance” between West and East was a consequence of neutrality. After 1955, senior politicians from the conservative People’s Party (ÖVP) and left-wing Social Democratic Party (SPÖ) – old foes cohabitating in a grand coalition – recognised that this constraint presented Austria with a unique opportunity to become a window to either side of the Iron Curtain. It was able to cultivate relations with its communist neighbours nearly as well as with its democratic peers and use this access to build bridges between these two worlds – as well as with the Non-Aligned Movement of states. This reached its zenith under the majority governments led by SPÖ chancellor Bruno Kreisky between 1970–1983, but other pathfinders included the ÖVP chancellors Julius Raab (1953–1961) and Josef Klaus (1966–1970).

The global recognition of Austria as a (notionally) safe place for government officials from rival spheres of influence allowed Vienna to host many institutions of international governance, including the United Nations, the International Atomic Energy Agency, the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe, and the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis. The city also became a global hub for spy activity given its lax espionage laws.

Ostpolitik

Relations between Austria and its Eastern Bloc neighbours had been poor over much of the immediate post-war era.

This began to change in the 1950s when Nikita Khrushchev replaced Joseph Stalin as premier of the USSR. Where before Austria had been a hostage of the USSR, the formalisation of Austria’s sovereignty warmed their relations.

This was arguably a form of Stockholm syndrome. Wartime reparations locked Austria into trade relations with the USSR to the point that Austria accrued a large surplus. Specifically, Austria was obliged to provide 60% of its oil reserves, the third largest in Europe at the time. As relations improved, Khrushchev agreed that some of the oil could be swapped out for other goods. In 1968, Gazprom and Austria’s flagship energy company OMV signed a long-term contract for the supply of natural gas, the first such agreement between the USSR and a democratic European state.

This, together with the détente between the West and USSR that began gaining pace in the 1960s, afforded Austria the opportunity to cultivate relations with its neighbours. The dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian empire and Austria’s subsumption into the Third Reich had resulted in its industrial sector being structurally reoriented towards Germany. But, in this brave new world, Austria could leverage its position as a “window between East and West” to provide Eastern Bloc states with access to Western technology and know-how. In exchange, it was possible to strike agreements on trade and visa-free travel (qualified in the case of the citizens of the Eastern Bloc).

Cooperation deepened further following the oil price shocks of the 1970s, as Western economies retrenched. A pillar of the economic policy of Kreisky’s SPÖ governments was guarding against unemployment. Thus, public contracts from state industry in East Germany and Poland became a source of sustenance for Austria’s state-owned industrial conglomerate, VOEST, especially in the iron and steel sectors. And as Western financial organisations were decreasingly willing to refinance the public debt of Eastern Bloc states, their Austrian counterparts stepped in to pick up some of the burden.

Austria was thus able not only to live with the Iron Curtain but also to profit from it. By 1986, there were some 2,000 Austrian companies specialised in trade with communist states, a unique competitive advantage (1). Some of these were front organisations, formed to hide the looted wealth of communist elites and their families.

None of this was uncontroversial, least of all in the West. For example, in 1960, Austria became a full member of the Belgrade Convention on the regulation of maritime traffic along the Danube. This was done without consulting Western governments, namely the USA and West Germany, which reacted with anger to it joining a regulatory framework of geostrategic significance – and that was dominated almost entirely by communist states.

Relations between Austria and the USA reached a particular nadir in 1981–1983 when the communist government in Poland imposed martial law to suppress nationwide protests by the Solidarity trade union movement. The presidential administration of Ronald Reagan consequently led an economic boycott of Poland. The Kreisky government, mindful of Austrian dependence on Polish industry and coal, did not join the sanctions regime, thereby throwing the Polish communist regime a lifeline. Indeed, Poland could use Austria to circumvent sanctions on dual-use technologies, for example.

More generally, there was often a sense that Austria was using neutrality as cover for double-dealing. This image was reinforced by scandals such as the Noricum affair, which saw managers of a subsidiary of VOEST illegally selling howitzers to both sides in the Iran-Iraq war.

This was true to some extent but overlooks the fact that Austria’s neighbourhood policy, as fully elaborated by Kreisky, was values-based. The thinking was that it was only through bilateral exchange and targeted integration that future conflict could be avoided and improvements to democracy and human rights effected. Austria, on account of its neutrality, could only really rely on dialogue and incentives to influence its communist neighbours.

This was achieved not only through economic cooperation but also by the strengthening of cultural ties at odds with communist ideals. For example, Austrian cardinal Franz König paid regular visits to liaise with his counterpart in Poland. The Austrian Literature Society (ÖGL) received secret funding from the US CIA to distribute particular books to libraries in the Eastern Bloc, to which it had privileged access.

Neither was Austrian neighbourhood policy toothless or risk-averse. For example, the country was a safe haven for tens of thousands of anti-communist dissidents throughout the Cold War. Express support was even given by the government to dissident groups, such as the Charter 77 movement of future Czech President Vaclav Havel.

Furthermore, it positioned itself as a transit hub for asylum seekers and emigres from the communist space, permitting entry to tens of thousands of Hungarians in 1956, Czechoslovaks in 1968, Poles in 1980–1981 (albeit to a lesser extent) as well as Soviet Jews from the 1970s. Such steps were often preceded by flipflopping, but seriously damaged relations with its neighbours, especially Czechoslovakia.

Doubling down

The only development which Austria profited more from than communism was its collapse. At the end of the 1980s, like many states, Austria was not agitating for the transition that was coming, hoping instead for gradualist reforms. Nonetheless, as communist regimes began to fall in 1989, Austria assumed a symbolic role. Most famously, the ÖVP foreign minister Alois Mock joined his Hungarian counterpart Gyula Horn in cutting down the wire fence along their shared border, whereafter a large picnic was held.

The collapse of communism fundamentally redrew the political geography of Europe. Where before Austria was a frontier state in a geopolitical grey zone, suddenly it became a gateway in the centre of the continent. And although it had not been under the yoke of the USSR, it was a hostage of sorts. In 1974, it was permitted to join the European Economic Community (EEC) but was prevented due to its neutrality from participating in the political integration that was forming the basis for the European Union. In the wake of the dissolution of the USSR, in 1995, Austria was finally able to accede to membership of the EU.

Under these circumstances, Austria’s neighbourhood policy refocused on three objectives:

1. Recognition of sovereignty of new states

After 1989, numerous new states were variously emerging from the USSR, Yugoslavia, and Czechoslovakia. Successive Austrian governments, especially the grand coalitions between the SPÖ and ÖVP in the 1990s, were among the foremost advocates of their rapid recognition by the international community. This was in direct continuity with the stance during the wave of decolonisation in the 1960s, when the government insisted that the international community respect the right of national groups to self-determination, forming their own states by democratic means.

2. European integration

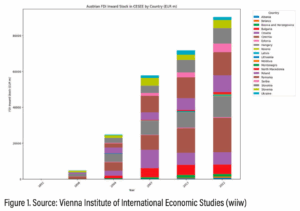

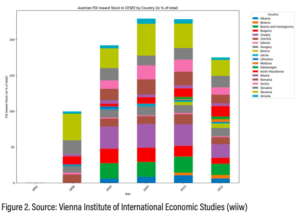

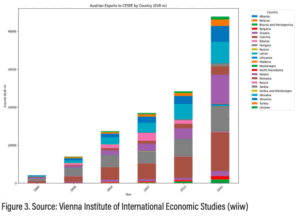

A priority for Austria was the integration of the states of the former Eastern Bloc and Yugoslavia into the European economic and institutional architecture, including the European Free Trade Area (EFTA), the EEC, and then the EU. Austria was no leader in this regard, partly because as a medium-sized member state it lacked the clout – but it was a vocal advocate. It was no coincidence that official accession negotiations began in the second half of 1998 when Austria held the rotating EU presidency. Deepening integration and facilitating convergence had material benefits for the Austrian economy, as its financial institutions and corporates spearheaded foreign direct investment into the region, and trade relations strengthened (see Figures 1–3).

Currently, Austria is particularly vocal in lobbying for the EU membership candidacy of Bosnia and Herzegovina. At the end of 2023, it briefly held up the launch of membership negotiations with Ukraine and Moldova in order to ensure that Bosnia would be included. Accordingly, in March 2024, the European Commission recommended that accession negotiations begin.

3. Security

Security was not a factor in the states of the former Eastern Bloc, the democratic transitions of which were peaceful. However, it was of great significance in the states of former Yugoslavia, where Austria assumed an important role in attempts to defuse hostilities amid the outbreak of the Balkan wars. Indeed, the SPÖ-ÖVP grand coalition at the time was very robust in its diplomatic approach, using Austria’s membership of the United Nations Security Council to table resolutions imposing a weapons embargo and economic sanctions on Yugoslavia as well as establishing a UN peacekeeping force and safe zones. Austria insisted that peacekeepers be authorised to use force to protect safe zones and uphold ceasefires, but this was denied, arguably leading to atrocities such as Srebrenica.

Since the 1990s, the security dimension has grown in importance for Austria. Unlike Germany, most refugees who arrived during the Balkan wars were permitted to stay in the country after the end of the conflict. According to official statistics, as of 2022, there were approximately 400,000 citizens of former Yugoslav states (plus Albania) resident in Austria – some 4.5% of the population (2). This is before Austrian citizens with origins in the region are counted. Thus, if armed conflict were to reoccur in the region, it could have direct implications for Austria’s internal security.

Unwanted, unneeded?

Over the past 20 years, Austria’s geopolitical influence in CEE has declined despite the growth of its economic clout. There are three reasons for this.

1. Decline of engagement amid changing regional dynamics

As 11 former communist states acceded to membership in the EU, Austria can no longer act as a patron in the same way. Strategic decisions are taken within the forums of the EU, rather than on a bilateral basis. Thus, Austria is a peer that is unnecessary for bridge-building in the same way, unlike in the past.

Austria does have a multitude of engagements with its “Central European community of interests,” which it conducts “horizontally” – namely, through subregional formats – to assist in the formulation of joint policy positions at the European level. One forum that proved especially successful was the Vienna Initiative, which was established amid the 2009 financial crisis to coordinate policy responses as the debts of CEE banks – Austria’s foremost among them – deteriorated. The format was effective to the extent that it was reconstituted in 2012 and remains in place to this day.

Other formats that it has taken the lead in establishing include the Central European Initiative (1989), which sought after the Cold War to reestablish governmental, parliamentary, and business connections across CEE; the Salzburg Forum (2000), a biannual conference of interior ministers from Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czechia, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia; the Central European Defence Cooperation (2010), an annual conference of defence ministers from Austria, Czechia, Hungary, Slovakia, and Slovenia, with Poland assuming observer status; and the Austerlitz format (2015), which comprises Austria, Czechia, and Slovakia, and focuses on identifying joint initiatives and interests more broadly.

Elsewhere, in 2011, the European Council adopted the Strategy for the Danube Region, which was formulated by the nine states of the region, including Austria, and focuses on strengthening infrastructural, environmental, economic, and institutional development.

In 2016, Austria became a member of the Three Seas Initiative, an intergovernmental format which plans to develop north-south transport and energy infrastructure in the CEE member states of the EU.

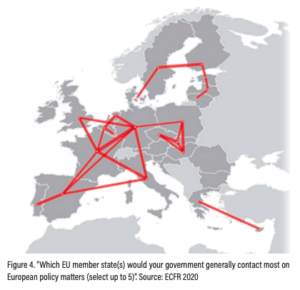

Although these formats reflect Austria’s intensive engagement with CEE, they are piecemeal and uneven. Austria wants to be present, but leadership is lacking. It has avoided engaging with forums that are more controversial: it briefly flirted with the idea of joining the Visegrad Group of Czechia, Hungary, Slovakia, and Poland, but ultimately did not do so. The failure of Austria to cultivate influence is demonstrated by a survey conducted in 2020 by the European Council for Foreign Relations, which found that Austria is not preferred as a bilateral point of contact on EU matters by any of its peer member states (see Figure 4) – although it is regarded as punching above its weight in terms of influence (3).

In the meantime, other CEE states have increasingly dictated the regional agenda as their own geopolitical profiles have grown. Poland has become one of the most important member states not only of the EU but also NATO, with its military set to become the largest land army in Europe by 2026. Enlargement of the EU is high on the foreign policy agenda of the liberal coalition formed by the Prime Minister and former European Council President Donald Tusk in December 2023. Elsewhere, Hungary has become a major geopolitical influencer under the government of Prime Minister Viktor Orban, who is a global poster child for illiberal populism.

2. Confused security policy

Since the end of the Cold War, and especially since Russia’s invasions of Ukraine in 2014 and 2022, security has topped the agenda of most CEE states. Yet Austria has very little to contribute in this regard. It maintains its neutrality despite having been entirely hollowed of meaning. Austria may not be a member of a military alliance (i.e., NATO), but it is a member of a political union (the EU), formulating and implementing common foreign and security policy.

Nor does its defence policy exist in a vacuum. The EU Treaty provides that, in the event of an invasion of Austria, its fellow members – nearly all of which are part of NATO – will be called to its defence. In 2024, Austria joined the European Sky Shield Initiative, which was established by Germany after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine to improve air defence. Austria’s armed forces participate in European battlegroups alongside NATO units. Austria is thus protected by NATO, as well as partly integrated into the structures of its member states; yet its political class insist upon the continuation of neutrality.

At the same time, Austria is regarded as maintaining uncomfortable proximity to the Russian Federation. It is one of the few European states that has failed to reduce its dependence on Russian gas, the provision of most of which remains governed by the long-term contract OMV signed with Gazprom in 1968. The contents of the contract are classified but take-or-pay clauses confine OMV to accepting the shipments because it is legally obliged to pay for them regardless.

Within Russia, according to the Kyiv School of Economics, Austrian investors have chosen disproportionately to continue their operations, hoping that geopolitical tensions will ease (4). Chief among these is Raiffeisen Bank International (RBI), which, in being the Western bank with the deepest penetration of the Russian market, handles half of international payments in and out of the country (5). In an echo of the 1980s, this has attracted the ire of the USA in particular. The impression, fair or otherwise, is that Austria is not an honest broker despite its neutrality.

This has resulted in Austria actively being sidelined in Ukraine, even as it took the lead in the provision of humanitarian aid. Where in the 1990s the Austrian government led in attempts at conflict resolution, taking decisions that were geopolitically wayfaring, it has shown no such strategic resolve in Ukraine and is unlikely to be sought after during the reconstruction process.

3. Domestic politics

The composition of the Austrian government has invariably influenced its neighbourhood policy. Historically, the ÖVP is the most Atlanticist party as well as having been the strongest advocate of EU membership. The SPÖ, on account of the foreign policy pursued by Bruno Kreisky’s governments, understood itself as pro-European but was more sceptical of political integration. Furthermore, it was particularly focused on cultivating positive relations with countries outside the Euro-Atlantic orbit.

When the two parties formed a grand coalition in 1986, the ÖVP secured the ministerial portfolio for foreign affairs, which it has retained almost continuously since then. While the chancellor’s office, which was headed by the SPÖ between 1986–1999 and 2006–2017, respectively, is important for foreign policy, diplomatic expertise and departmental implementation has been monopolised by the ÖVP. For much of the period since 1989, this did not really matter, as there was a broad bipartisan consensus on neighbourhood policy.

Yet since the 2000s, the quality of Austrian foreign policy has declined as politics has become increasingly parochial. The reason for this is the steady erosion of the formerly monolithic vote shares of the ÖVP and SPÖ, the main beneficiary of which has been the far-right Freedom Party (FPÖ). The foreign policy of the FPÖ has changed over the decades; it has always been nativist and Eurosceptic, but where in the 1990s it supported Austrian membership of NATO, it has since become one of the loudest apologists for neutrality. This crudely masks its sympathies for illiberal, authoritarian states such as those led by Russia’s Vladimir Putin, Hungary’s Viktor Orban, and Serbia’s Aleksandar Vucic.

In responding to the threat posed by the FPÖ, the ÖVP has approximated some of its policies in CEE. Over the past decade, the southeast of the region has been one of the main corridors for asylum seekers and illegal migrants, with Austria serving once again as a gateway into Western Europe. In December 2022, as illegal immigration reached historic highs and the poll ratings of the ÖVP languished at low levels, the government vetoed the applications of Romania and Bulgaria to join the Schengen area of free movement, arguing that their borders were insufficiently secure. A compromise on the issue was reached a year later, with controls at air and sea borders being lifted, while those along land borders remained in place.

However, the signal was clear: Austria had weakened its reputation as an unequivocal champion of EU enlargement and the deeper integration of new member states. Insult was added to injury owing to dealings elsewhere. The government had originally also planned to veto the Schengen application of Croatia but refrained from doing so shortly after the Croatian government pledged to expand its infrastructure for the export of liquified natural gas to accommodate Austria’s needs. A confrontation with Hungary was avoided despite it being the main entry point of irregular migrants into Austria, with the Hungarian authorities systematically encouraging passage.

Quo vadis?

In CEE, Austria occupies less of a leadership role than that of a partner. This remained the case both before and after the Cold War. Cooperation in the areas of economy, culture, and science has always been regarded by the Austrian political establishment as the best way of delivering regional integration and development. Governments across the decades, at least until the 2000s, proved skilled in seizing opportunities to increase their regional engagement to the benefit of the Austrian economy. This has not always been uncontroversial.

In relative terms, Austria’s influence in CEE has declined. It remains an important economic stakeholder in most states of the region, especially given the size of its investment footprint. It also remains important as a patron and supporter of states in the Western Balkans, the foremost of which is Bosnia and Herzegovina.

However, as the former states of the Eastern Bloc settled into their membership of the EU, gaining influence in their own right, the Austrian political class lost the proactivity it showed until the turn of the millennium. Furthermore, its slowness in geopolitical adaptation and perceived willingness to engage in double-dealing has increased scepticism, especially among CEE states where security is a leading strategic concern.

This dynamic could deepen in the future. With parliamentary elections due in September 2024, the FPÖ is polling in first place, with a strong chance of forming, if not leading, the next coalition government. The FPÖ has long entertained the idea of joining the Visegrad Group. At the very least, it is actively taking steps to strengthen its relations with like-minded parties in CEE.

In July, the FPÖ joined the Patriots for Europe bloc established by Viktor Orban’s Fidesz party in the European Parliament. Illiberal parties either occupy or have a strong chance of occupying government in most other CEE states in the EU. With its similar ideological outlook, it is possible that the FPÖ will preside over a strengthening of Austria’s relations with its CEE neighbours. However, such alliances will not be a force for the deepening of European integration more generally, but regression.

Marcus How is head of research & analysis at ViennEast Consulting in Vienna. This article was originally published in the working paper “Austria and Central Europe: Foreign Policy, Migration, and Energy Strategies” by Prace IEŚ.

References

(1) A. Resch, Der österreichische Osthandel im Spannungsfeld der Blöcke, 2010.

(2) https://www.statistik.at/statistiken/bevoelkerung-und-soziales/bevoelkerung/ bevoelkerungsstand/bevoelkerung-nach-staatsangehoerigkeit/-geburtsland.

(3) https://ecfr.eu/special/eucoalitionexplorer/.

(4) https://leave-russia.org/?flt%5B131%5D%5Beq%5D%5B%5D=424.

(5) https://www.ft.com/content/1cea1f08-83ac-4471-9fa4-1cdfcc86fcb0.